When Interior Design Is Life or Death

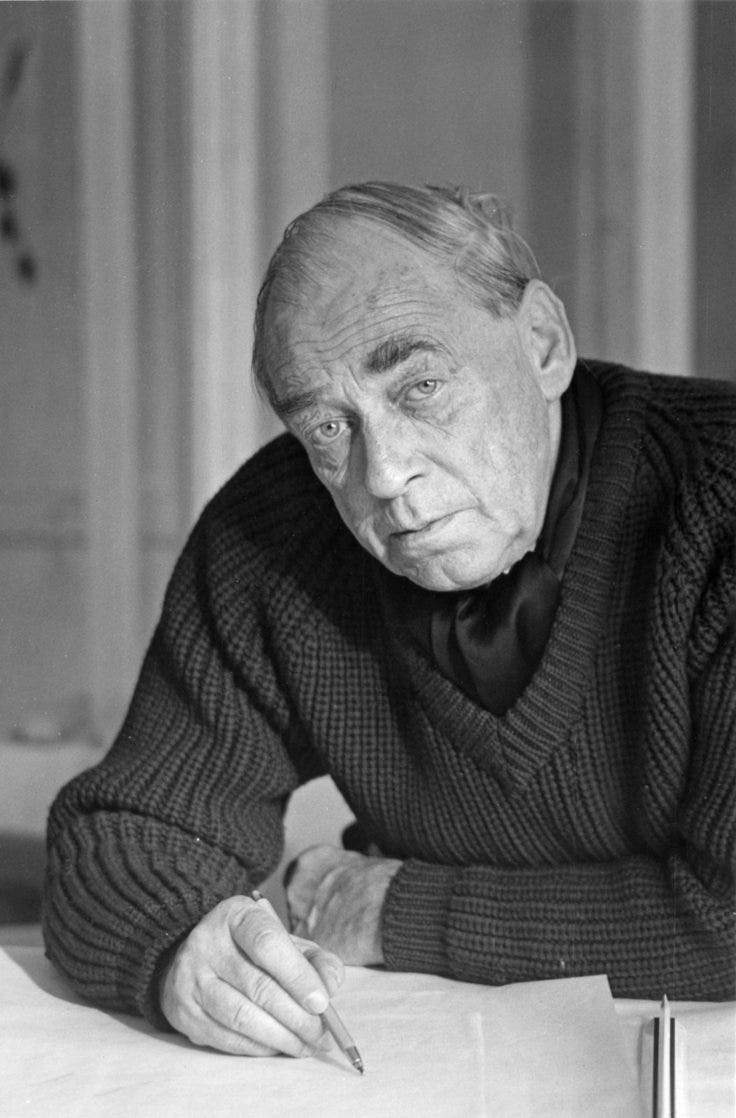

How one architect's vision for a tuberculosis sanatorium changed the way I think about designing truly human spaces

A Hospital That Listens

Pre-startup, when I was still working full-time in the NHS, my mornings had a kind of ritual to them. Like many Londoners, I caught the same train each morning — for me it was the 7:13am Overground train — Whitechapel to Denmark Hill. Coffee in hand, headphones in, half-awake but already bracing myself for the forty-patient ward round ahead. It was during one of those commutes that I first heard about a hospital designed for emotion as much as practicality.

Monocle on Design was playing in my headphones, but I wasn’t fully tuned in until something caught my attention. The host was talking about a sanatorium in rural Finland, designed by Alvar Aalto in the 1930s. A building where the ceiling colour was chosen to ease the eyes of patients lying in bed. Where the chairs were angled to support the lungs. Where even the light switches were designed to feel gentle in the hand.

That was the first beat of the butterfly’s wing — small, but it permanently shifted the way I thought about healthcare spaces from that day forward.

The contrast between what I was hearing and where I was headed was stark. The hospital I worked in — like most — was built for function, not feeling. But this was something else entirely. It wasn’t just architecture, it was care in physical form. Unspoken, but loud as hell at the same time.

That was my entry point into Aalto’s world. Since then, I’ve become a fan of Artek, the furniture company he co-founded. I have several of his pieces around my home — and they carry the same quiet intelligence. In fact, the desk that I type this from is an Artek Kaari desk, purchased secondhand a few years back. They don’t shout, they don’t posture or demand attention. They just... support, effortlessly, with a quiet, bold confidence. Like they were designed by someone who obsessed over every centimetre of detail. Deeply human.

Designing for Life

In the 1930s, there was no cure for tuberculosis. The only treatment offered was rest, good food, fresh air, and sunlight. So when Alvar, just a young architect at the time, and Aino Aalto were commissioned to design the tuberculosis sanatorium in Paimio, they knew the building itself had to do some of the healing.

Every detail was intentional:

Patient rooms faced the sun.

Balconies were designed for daily “air baths.”

Surfaces were easy to clean, but never harsh.

Colours were chosen to soothe, not stimulate.

This was more than architecture — it was environmental medicine. Scientific research has since confirmed the importance of things like access to sunlight and fresh breathing air during the healing process, but at the time, placing these interventions front and centre was close to revolutionary.

A Chair That Helps You Breathe

One of the most iconic pieces of furniture to come out of the Paimio project was the Paimio Chair — a bent plywood armchair with a smooth, almost floating form.

But it wasn’t just a beautiful object. It was designed with a specific purpose: to help tuberculosis patients breathe more easily.

The backrest is angled to open the lungs and reduce strain on the body. It wasn’t about ergonomic buzzwords or sleek vibes — it was designed specifically for the act of breathing. That basic, involuntary rhythm we only really notice when it’s taken away.

The chair also feels gentle. There’s no metal, no hard edges. It’s made from bent birchwood (a wood type native to Finland and a process pioneered by Artek) — light, flexible, warm to the touch. In a time when hospitals often looked like sterile factories, the Paimio Chair offered a different vision: one where care and comfort could coexist.

It’s easy to forget that furniture can be emotional. That a chair can make someone feel safe, seen, at ease. The Paimio Chair does just that by supporting a core regulation mechanism: your breath.

The First Wellness Architect

Aalto didn’t call himself a wellness designer or a sensory designer. But he was doing it long before it became a category. He believed that buildings should serve people, not impress them. That spaces should respond to the senses. That design should support life, not distract from it.

He worked with materials that aged well. Used curves where others used corners. Brought nature in without forcing it. His buildings aren’t just good-looking — they’re good for you.

You could call it soft modernism, or intuitive humanism — but really, it’s just good design. The kind that understands that the feeling of the space you’re healing in is equally as important as the treatment you’re receiving in it.

Why This Still Matters

I think a lot about how little most healthcare spaces today reflect what Aalto knew almost a century ago. Cold lighting. Shiny plastic chairs. Echoey corridors. Spaces that do little to support the mind or body.

We know better now — about trauma, sensory overstimulation, the impact of the built environment on stress and recovery. And yet we keep building clinics like they’re health factories.

Paimio is a reminder that design can do more. That healing can start before the medicine arrives. That the shape of a chair, or the light in a room, might be the difference between feeling like a number and feeling like a person.

Final Thought

Alvar Aalto didn’t just design for the body. He designed for the nervous system.

And in doing so, he gave us a template for care that still feels radical — because it feels.

Sometimes, design doesn’t need to shout to change everything. Sometimes, it just needs to help you breathe.

-

P.S. — Liked this piece? Subscribe for more, or drop a comment below and tell me your favourite part. I actually read them.

Designing Emotion: A Biological Guide

👀 If you enjoy this piece, tap Subscribe to get future essays in your inbox — and share it with a friend who’d like it too. It all helps!

I’m trained as an Architect and I now

Work in Healthcare so this feels very providential lots of thoughts and learnings to take away as well as areas of further study. Thank you for writing this.