i built a vr app that learns your nervous system

wellvrse® — an exploration in wellbeing, curiosity and design, treating the nervous system as a canvas

Building this has been a labour of love. Emphasis on labour.

If people actually knew the sheer volume of work it takes to go from idea to product — the missteps, the doubts, the pivots along the way — most would never even begin. It’s the toughest task I’ve ever taken on. It demands creativity, mental resilience, business sense, and a kind of stubborn openness you can only summon when you wholly believe in something.

I still remember the precise moment when the idea came to me. A sunny spring morning in my Brixton flat. It kind of felt like a butterfly gently landing on my fingertip. Like the idea chose me almost.

We hear the founder “lightbulb moment” stories all the time. That’s the shiny part — the bit the media glamorises. That initial rush is amazing. The excitement, the possibility. But it does inevitably pass. At times, I felt like I was surviving on mere glimmers, without that rush, it’s sometimes easy to forget why you’re doing this thing. This is the phase that breaks most, and I understand why. When you’re pouring your heart, soul, and savings into something, the knock-backs, the rejected funding applications with no feedback, the “this won’t work”s start to feel increasingly personal.

With all that being said, there’s not a single other thing I’d rather be working on. There’s a quiet, settled certainty that this thing we’re building can help people in new ways, could shift the way we think about care.

so, why vr?

I watched an interview with Earl Sweatshirt recently, where he said something along the lines of you need to be dumb to create. Maybe dumb is too far, but I’d agree naivety was more helpful than harmful in those early moments.

In 2021, coming off the back of the pandemic, with Facebook’s rebrand to Meta and a renewed focus on digital life, the metaverse boom was at its height. It felt like the industry to be in, the next frontier to explore—people were comparing its trajectory to smartphones in 2007/8. That’s what initially caught my interest.

But as anyone who’s studied the history of tech knows, with every boom comes a bust. The bubble popped, the money stopped flowing, and sentiment around VR flipped almost overnight from next big thing to “gimmicky money pit.” Startups were pivoting or shutting down. VR apps weren’t profitable.

Things looked bleak but something about VR still made sense to me. Even after the “metaverse” moment fizzled, the hardware remained: cheaper, more capable, and backed by billions in investment. Crucially, it still lacked a defining use case. That absence felt like an open canvas.

Designing for the nervous system inside VR offers something rare: control. A headset is a closed environment, almost like a portable lab. It strips away variables and lets you construct experiences at the level of perception itself. Two senses (vision and hearing) are fully controllable, and a third (touch) partially through haptics.

space + visual logic

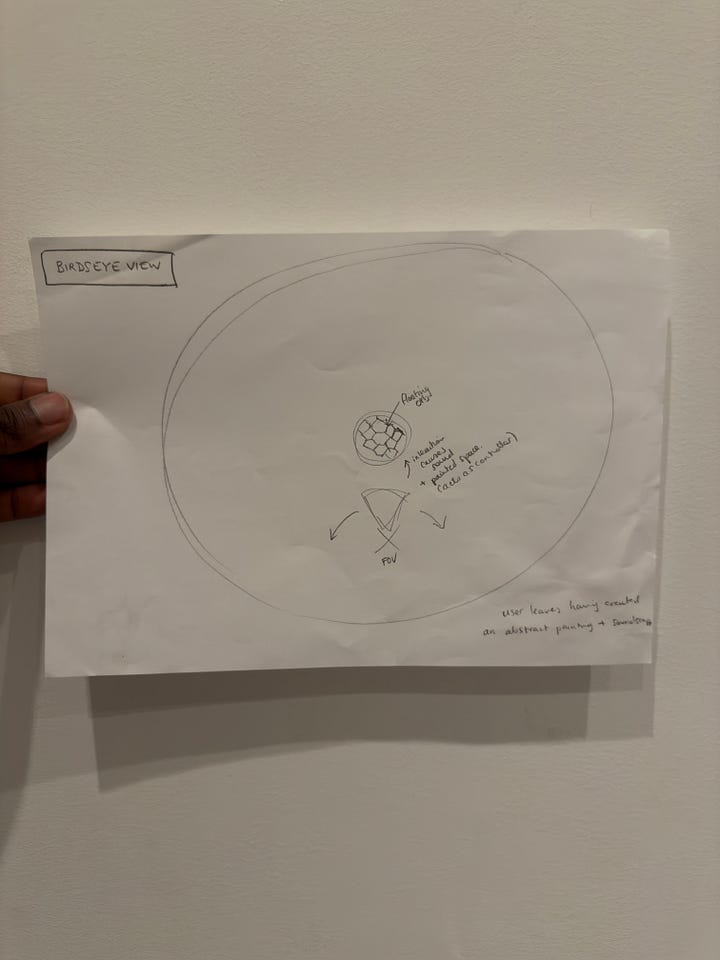

I started with a simple design question: how do I want the space feel?

Designing VR spaces can be tricky, especially as a novice. There are so many more considerations than a 2D space. Height, depth, width, shape. Freedom — are we allowing users to explore freely or restricting their movement? How will they navigate the space, and what affordances do I need to add to make it intuitive? Are we creating something analogous to reality or something otherworldly? All of these decisions had to start from understanding the goal of the environment, and I kept coming back to one word: safety.

I needed users to start from a baseline of feeling settled in the space, hopefully some familiarity, too. So the aim was to create the visual perception of safety.

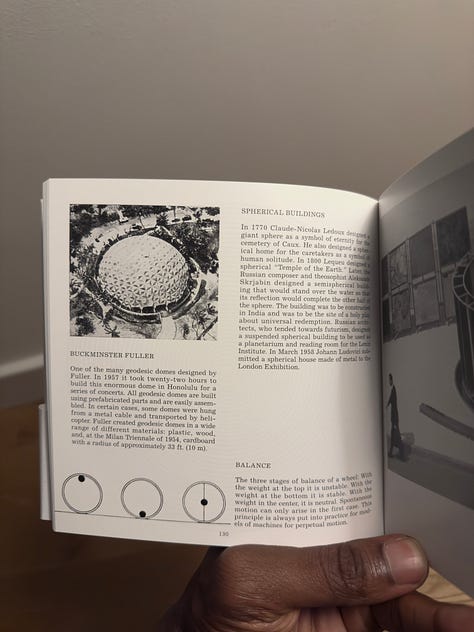

Circles, spheres and domes became recurring motifs. Igloos, enclosures, spaces that hold without trapping. Bruno Munari described the circle as the “perfect shape”—balanced, continuous, human. In fact, he wrote a book simply titled “Circle”. That became the architectural cue for Wellvrse: safety as geometry.

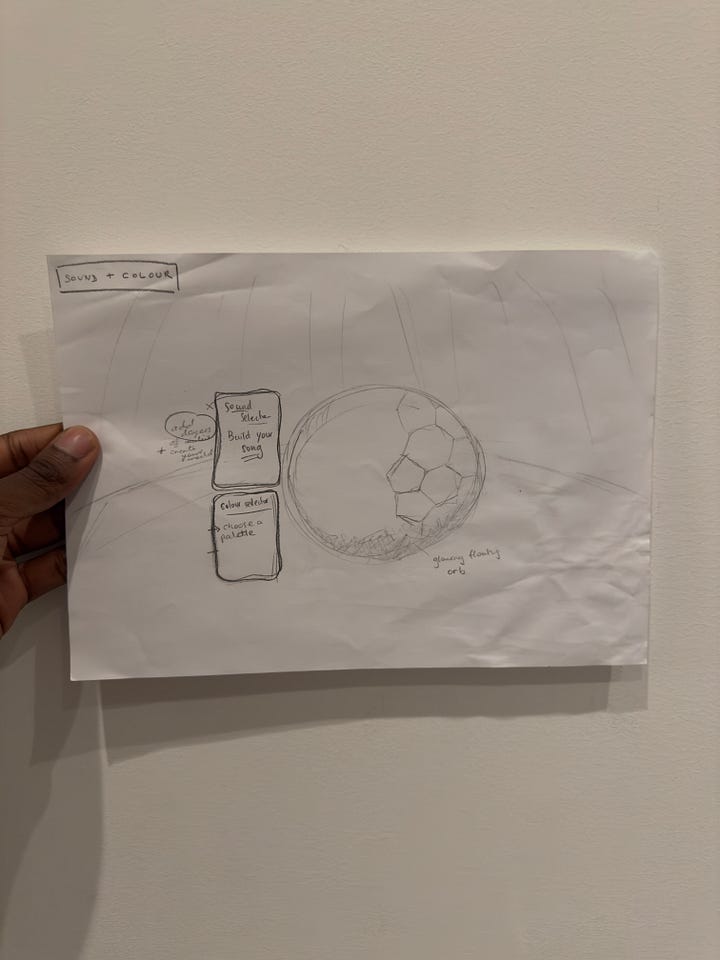

Colour was the next layer. The most basic element of vision, but also the most subjective. In nature, colour warns—the yellow and black of a wasp. In everyday design, we echo the same codes in hazard tape and caution signs. But colour is also deeply personal: the example I often give is that red can mean roses or blood, depending on who’s looking. That tension between universal signal and private meaning made colour the right first variable. A way of testing how differently nervous systems register the same input, and eventually, building a unique profile for each user.

sound design

If visuals provide structure, sound gives the environment its temperature.

A lyric from Central Cee stuck with me: “I’m used to falling asleep to the sound of sirens, so I don’t know if I like this change—it’s too quiet.” It captures the paradox of adaptation. Our nervous systems can learn to find safety in chaos, to the point where silence feels alien. That paradox became part of the design: quiet isn’t inherently calming, noise isn’t inherently destabilising. Context matters.

I was fortunate to work with music psychologist Dr Michelle Ulor of Kinos Studio to shape the sonic palette. From the start, I wanted to treat sound in two layers: hearing (passive, ambient sound) and listening (active, created sound).

We worked iteratively, testing different combinations until the palette felt distinct yet harmonious — stable enough not to distract, but varied enough to draw out preference. The point wasn’t to dictate how someone should feel, but to see what they naturally gravitated towards or reacted against.

Sound, like colour, carries layers of meaning that aren’t always easy to put into words. You might not be able to articulate why a certain tone unsettles you or why a certain texture feels grounding, but your nervous system registers it all the same. By keeping the palette neutral and non-intrusive, we created a kind of baseline — an environment where those responses could emerge without being forced.

Here are a couple of the stem group samples:

the wholi™ engine

Experiments in colour and sound are interesting on their own, but without a way to connect the dots they risk staying abstract. From the outset I knew the challenge wasn’t just to build experiences, but to make sense of the responses they provoked. That outcomes-focus is something I carry directly from my medical training. It’s also the role of WHOLI™ — the Wellvrse Holistic Observation Load Index.

WHOLI processes what happens inside Wellvrse: entry and exit questions based on tools like PHQ-9 and GAD-7, combined with interaction data from the headset, and eventually, biometrics. It’s the engine that turns raw responses into something structured: a dataset on sensory health and preference.

That’s where it becomes practical. Imagine a backend that plugs into Spotify to generate a de-stress playlist based on your actual nervous system responses. Or a clinic room where lighting and sound shift to your profile before you even step inside. The same system could tune workplaces for focus or help museums design exhibitions that feel different depending on who’s walking through. WHOLI makes sensory responses usable in daily life, not just in a headset.

It’s still early, but this is what moves Wellvrse from “exploratory art project” into something larger: a framework for understanding how design decisions land on the nervous system. Looking back, that’s what I was reaching for in those early days — I just didn’t have the language for it yet.

what’s next?

Wellvrse isn’t finished, but it exists — an actual digital product, not just an idea sketched in a notebook or pitched on a deck. There were plenty of moments when even I wasn’t sure it would add up, when the whole thing felt like it might collapse under its own weight. In a field where so many ideas remain abstract, simply getting to something real gives me enough confidence to shoot for the next target, even in the midst of uncertainty. And the more founders I meet, the more I realise that’s a trait they all have in common.

This process has never been about announcing a finished product. It’s about keeping a question open: what happens when you design directly for the nervous system?

The first answers are here — in circles, in colour, in sound — but they’re only beginnings. The real work is the cycle itself: refining, testing, failing, adjusting. That loop is the experiment.

In that sense, Wellvrse is both a prototype and a provocation. A reminder that healthcare doesn’t have to be confined to treatment rooms or policy documents. It can also be designed — through space, sound, and colour — as an environment that shapes how we feel, moment by moment.

Brilliant work man, well done!